SO478 - week 8

« Back to SO478These are my notes from November 14 for SO478 at the London School of Economics for the 2017-2018 school year. I took this module as part of the one-year Inequalities and Social Science MSc program.

The usual disclaimer: all notes are my personal impressions and do not necessarily reflect the view of the lecturer.

Social mobility and inequality

Readings

Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite by Shamus Khan (introduction)

A moving first-person account of upward social mobility. Highlights a trend (that I can personally relate to) where immigrant parents are okay with their own lack of social/cultural capital because they imagine their kids will, in some way, make up for that. Mentions the skewed nature of admittants to elite schools (Harvard’s definition of “middle income” is $110k-$200k which is really the top 5% …). Also briefly touches on the recent trend toward cultural omnivorism, where part of being privileged means being comfortable in any cultural environment.

Great quote:

They may claim otherwise, but colleges are truly “need blind” in the worst possible way. They are ambivalent to the disadvantages of poverty.

He also talks about meritocracy discourse and how there’s been a trend toward greater awareness of inequality & attempts to alleviate it. He isn’t nearly as critical as I would be here—I would treat it as a less of a demonstration of kindness and more of a defense mechanism on the part of the elite class, allowing a small amount of upward mobility from the lower classes in exchange for their consent—and seems to treat any negative consequences of meritocracy as due to drift (because the abilities being measured aren’t the right abilities) instead of as immanent. Piketty’s comments on meritocracy (from an interview with Mike Savage, coincidentally) are relevant here (referencing the founder of Sciences Po):

[…] now that we have universal suffrage, there’s a risk that basically the poor and the majority of the population will try to expropriate us, the elite. We have to display merits and our own standings so that it will be a completely crazy idea to get rid of us. So in a way it’s as if […] modern meritocracy discourse is invented as a way to protect the elite from democracy basically, from the universal suffrage.

Frédéric Lordon says something similar in Willing Slaves of Capital:

[…] With the eras of aristocratic and plutocratic legitimacy gone (at least in their pure forms), the contemporary mythogenesis of the university degree, as Bourdieu repeatedly insisted, struggles to hide its own indifference to content and its only true mission, which is to certify ‘elites’, namely, to provide alibis to the distribution of individuals within the social division of desire.

Immanuel Wallerstein also has an excellent take on this, in Historical Capitalism:

[…] The institutionalized meritocratic system helps a few to gain access to positions they merit and from which they might otherwise be barred. But it allows many more to gain access to positions on the basis of ascribed status under the cover of having gained this access by achievement.

Social Class in the 21st Century by Mike Savage (chapter 6)

I just read the whole book since I happened to have it already. My notes are all in Bookmarker.

There’s a quote from John Hills’ Good Times, Bad Times which is fairly relevant to the discussion of social mobility in chapter 6:

[…] If policy helps increase the chances of someone starting in a less privileged position to go up the social scale, that must mean that someone else’s chance of going down has to rise, which may include their own children, and does not then seem so attractive. While many favour increased upward mobility, few want to mention the increased downward mobility that has to go with it (in terms of relative positions, at least).

The Price of the Ticket (PDF) by Sam Friedman

On the downsides of upward social mobility. Challenges Goldthorphe’s landmark work on this field (which drew on surveys and concluded that upward mobility was a Good Thing) by focusing on the downsides of it (mostly int terms of the negative psychological effects on the subjects). Cites Bourdieu and Durkheim, among others. This paper raised some good points about why we shouldn’t uncritically support the idea of social mobility, but I kept waiting for the obvious conclusion—that we should destroy class hierarchies altogether—that never came …

Lecture

This lecture was given by Mike Savage, Professor of Sociology at LSE.

- quote from former Labour MP Alan Milburn on social mobility as a way of breaking integenerational transmission of advantage

- (thus it’s a limited, conservative, reactionary attitude that implicitly accepts the current class hierarchy)

- (what Nancy Fraser would have called “affirmative” rather than “transformative”)

- (what else would you expect from a Blairite I suppose)

- the more inequality there is in a society, the more important the idea of “meritocracy” becomes in order to justify it

- and since inequality is rising, there’s been an urgent focus on social mobility (often seen as a necessary condition for meritocracy)

- there’s a debate on whether social mobility is increasing or decreasing

- takeaway from this lecture: it’s very complicated, multifaceted, and difficult to measure

- be skeptical about anyone who tells you unequivocally that it’s rising/falling

- complications when measuring it include:

- which benchmark do you use? income, level of educational attainment, home ownership, ??

- which unit? individual, household, community?

- compared to whom? parents, grandparents, younger you?

- what time scale?

- individualist or structural approach (where you’re compared with others)?

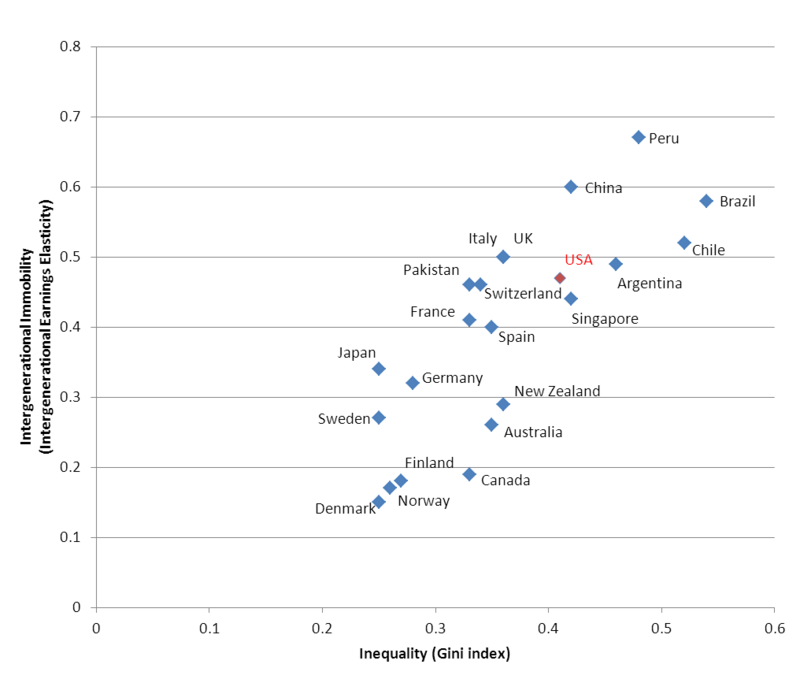

- The “Great Gatsby curve” from 2012, showing the relationship between Gini coefficient and intergenerational earnings elasticity

- (image from Wikipedia)

- shows the relationship you’d expect between inequality and social mobility

- possible reasons:

- in a more equal society, there’s less “distance” to travel and so it’s easier

- in a less equal society, the rich try to pass on privileges to their children (closure, pulling up the ladder behind them etc)

- Raj Chetty did research looking at social mobility rates for each birth year (presumably adjusted for inflation?)

- shows that the % of children out-earning their parents has been decreasing over time (since the 40s)

- measured in terms of absolute income (adjusted for inflation presumably, which is itself problematic)

- this graph doesn’t tell you the whole story, though; could be due to decline of wages overall, or economic growth (?)

- basically the point of showing us this graph is to illustrate the dangers of reductive thinking re: social mobility

- in the UK case, Blanden & Machin looked at social mobility among children in 1956 & 1970 (separating sons & daughters)

- produced some transition matrices showing that social mobility has decreased

- (incidentally, this is a good example of a structural approach as opposed to an individual one)

- another Chetty approach (w/ Saez, 2013): rank ordering of income compared with parents

- shows that social mobility (measured by income percentile) hasn’t really changed

- though college attendance gradient in decline (probably due to increased tuition fees …)

- this is an example of a relative approach to social mobility

- we should reconsider the relationship between Gini & social mobility

- not a standard causation -> correlation story

- if we consider the wealth of the countries involved (in the Great Gatsby graph) you see a pattern

- the more equal & mobile countries on the bottom left (Scandinavian) are also quite wealthy

- and the less equal & mobile countries on the top right (South American) are relatively poor

- Goldthorpe (who’s contributed a lot to the study of social mobility) emphasises that we need to look at relative social mobility, especially in periods of economic change

- when you have skills-biased technological change, education will be a factor in social mobility

- e.g., in China: in the past few decades, modernisation has resulted in a lot of upward mobility

- but that doesn’t mean that the children of the poor today should expect the same upward mobility

- it just means that at a certain time in the past, education was used as a filter to fill posts in the new economy

- (note that Goldthorpe is looking at occupation-based social class here, not income)

- graph of upward & downward mobility: shows that the total amount of mobility has gone up

- and ofc upward/downward are mirror images of each other

- reason for increasing downward mobility: changing composition of labour market?

- open Q: what are the downsides of using Goldthorpe’s class structure for our understanding of social mobility?

- there are obviously lots of caveats (like what if you have a lower income but the same lifestyle, and what if a partner provides for you)

- in an era of rising inequality, should we be looking beyond absolute social mobility?

- the economist approach to social mobility: looking at income (as opposed to the class model used in sociology)

- the economists’ human capital model assumes fluid mobility due to skills

- whereas the Weberian/Bourdieusian approach considers social class as a way of excluding people below you

- draws heavily from feminist theory (think the “glass ceiling”) and homophily theory

- Friedman (from the third reading) proposes the idea of a class ceiling in which the highest earnings are reserved for the upper class

- in a complementary vein, Khan (first reading) proposes that education is at least partly performative—a way to sustain the privileges and know-how of elites

- conclusion: there is definitely some social mobility

- just not enough to justify existing inequalities & this idea of meritocracy

- plus ofc lots of closure

Seminar

This was a pretty unstructured one where we mostly talked about our own personal experiences with social mobility. Some takeaways:

- the way we look at social mobility in terms of a hierarchy: how much does that influence our conception of it?

- as in, does it make us more likely to want to try to “rise” in it

- when there isn’t necessarily an a priori reason we need to?

- my own trajectory is a pretty good example: turning away from the possibility of an extremely well-paid job at Google to do an (essentially unpaid) startup and, now, spending most of my savings on a masters degree without the expectation of a higher income later on

- which really comes down to me not being a good member of Homo economicus, and instead prioritising things other than income (can u imagine)

- you could also look at it as me still playing into the logic of capitalism, just eschewing economic capital in favour of the cultural capital I theoretically get in exchange (not a great exchange rate tho tbh)

- institutionalisation of privileges as a field advances

- e.g., tech, where as more and more people pour in to the field, the goalposts get raised (you need more credentials etc to get people to take you seriously, whereas initially it was perhaps more open)