February 10, 2019 (1619 words)

::

On Dynasty Warriors, and the political implications of treating other people like NPCs.

Tags: games, ideology, class-struggle

This post is day 41 of a personal challenge to write every day in 2019. See the other fragments, or sign up for my weekly newsletter.

The good news is that the miasma of illness that’s been plaguing me the last few days is finally starting to lift, so today’s blog post will have more original content. The bad news is that my level of self-pity remained high enough that I allowed myself to play several more hours of Dynasty Warriors as consolation, and in between that and reading a somewhat life-changing book, I didn’t have time to work on any of the blog posts I’d been planning. So here’s today’s post on Dynasty Warriors as an allegory for capitalism.

For some background context: Dynasty Warriors is a fairly popular hack & slash game, set in ancient China (around 200 AD) and invoking characters and events from ancient Chinese folklore. The version I’ve been playing, DW8, is one- or two-player and can be played on a variety of consoles (I played it on the Switch). You can play as one of many mythical Chinese fighters, mostly from one of the three kingdoms, and your job is to help your side win various battles, eventually leading up to the kingdoms’ unification.

The game gives you a sense of the absolute brutality of war, as well as its pure senselessness. The breadth of characterisation is truly remarkable: there are dozens, maybe even hundreds, of named characters, many of whom are based on historical figures, though perhaps exaggerated in terms of physical features and ability (the women of the game are all granted preternatural fighting skills and, of course, the usual implausible proportions revealed through highly combat-inappropriate clothing). But there are many more unnamed characters, who make up the bulk of the soldiers on the battlefield: the Chinese peasantry, who have been inexplicably drafted into someone else’s war. Other than occasional variations in the weapons they carry, they are interchangeable, and their fate is to die nameless, alone, in a faraway land, simply because some warlords are unable to settle territorial disputes on their own.

Before battles start, you can sometimes talk to the peasants who’ve been drafted into your army. You can’t say anything yourself, but you can hear a litany of complaints from these reluctant soldiers. They’re injured. They miss their family. They don’t understand the reasoning behind this battle.

Most of them are not there willingly. They want to go home, but they can’t, because desertion can be punishable by death, and in any case this is probably the safest option in a world that’s been violently upended by neverending war.

I would love to read something from the point of view of the actual peasants who were drafted into these wars. Like Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which explores the events of Hamlet from the perspective of two minor characters in the original, but set in ancient China. What was life like for these untold numbers of peasants, who went from peaceful lives lived on their own terms, to little more than cannon fodder, their already brief life expectancies shrunk to the length of the next battle? The warlords are commemorated with massive statues in their image, and their names are recited in hushed myths passed down the generations. But the millions who died so that these warlords might attain a little more power are forgotten to history. No statues are built, and no names are remembered.

That’s how it was in real life, and so it is in the video game reenactment. The game has three modes: “story mode”, which follows various hypothetical storylines (some based in pre-existing myth, some entirely made up); “free mode”, which lets you re-enact a particular battle; and “ambition mode”, where you start from scratch to build your own empire. Ambition mode is where I’ve been spending most of my time. You choose a character, then seek out battles where you can find loot or convince “allies” to join you after defeating them in combat. In the process, you can use the supplies and money you acquire to improve your base camp, including building a monument to your own personal glory. You’re the hero of this story - all the other characters are just members of your army, and even the ones with fleshed-out backstories and characterisation exist only to obey your command.

They’re NPCs, after all. They don’t have agency. Having a large army, led by skilled allies, will help you win more complex battles, which will allow you to accumulate more gold and building materials, which in turn will allow you to expand your empire. Who cares what the people in your army would actually want to do, if you’re deriving so much value from having them serve you?

Of course, this is borderline ridiculous analysis. The NPCs are not actually worthy of our sympathy, because they are literally just manifestations of an algorithm. They’re pixels on a screen, and it would be silly to anthropomorphise them. It’s just a game, in the end.

But as I’ve said in my fragment on RuneScape, no game is ever just a game. The implicit rules that underpin the mechanics of a particular game universe are reflections of reality, as it is with any other cultural product - the books we read, the shows we watch, the advertisements we see. Even the most outlandish fantasies contain shards of the shared reality under which we live, if only because the production of these fictional worlds occurs in our world. And in reflecting these fragments of reality, they also reinforce them. Every game is driven by its own peculiar ideology, and any unwitting player who wishes to progress in the game must behave according to its precepts. Spend enough time playing the game, and that ideology can leak out into real life.

What happens when you treat people IRL as if they’re NPCs in a video game? Where you are the only true subject - the hero of the story - and all other people are algorithmically-generated illusions who exist only to further your endless ambition?

What happens is that you become the ideal vessel for the reproduction of capital. Your success as a capitalist depends on the degree to which you see other people as NPCs. If you want to grow quickly, you’ll have to be ruthless; employees are nothing but their labour-power, appreciated solely for the surplus value you can extract from them, and to be jettisoned the moment they cease to be useful in your neverending quest to expand your empire. And like the peasant soldiers in Dynasty Warriors, they may resent their situation, but they also know that it would be foolish to leave, no matter how much they’d rather pursue self-actualisation on their own terms. It’s simply not an option.

You never get to play as the peasants, in Dynasty Warriors. The fate of these figurants is not your concern, because you can transcend their pitiable plight. You know the hierarchy is unfair, but at least you can climb to the top of it, where things look much sunnier. And once you get to the top, you’ll never look back, because the challenges of constantly expanding your empire are just too damn consuming: building more facilities, recruiting more allies, upgrading your weapons. Wealth and power beget more of the same, ad infinitum.

I first read Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead as a teenager and for a brief period of time, I was completely enamoured with it. I wanted so badly to believe in her vision of the world, where there was a clear demarcation between The Real Heroes Of The Story (i.e., myself, and people I respected) and all the unwashed NPCs who made up the rest of humanity.

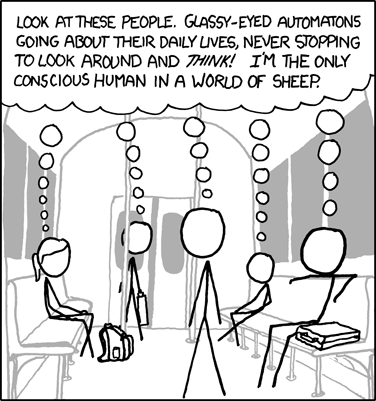

An xkcd comic illustrating exactly how stupid this perspective is.

An xkcd comic illustrating exactly how stupid this perspective is.

It’s the standard solipsistic fantasy: you only experience the world through the lens of the self, and it’s tempting to seek refuge in the possibility - however epistemologically shaky - of the superiority of the self compared to the other. After all, you cannot prove that others are selves just as real as you.

But you can’t prove they’re not, either. You have to choose what to believe, one way or the other.

In case the political implications of that choice are not obvious, consider that parts of the far right have latched onto “NPC” as an insult for people they don’t consider to be true subjects, and who are thus not to be included in whatever nationalist utopia they imagine for themselves. And for the politics-as-usual crowd, who are more horrified by the resurgence of the left than they are by the rise of the right, you get a sense that they think of themselves as heroes-in-waiting, itching for the chance to restore sanity to the liberal order and infuriated when their constituents aren’t them the gratitude they deserve. For career politicians, the game is about accruing power, and the voters who get them there are just so many NPCs.

What would it mean to treat other people as fully-fledged political subjects? To recognise that other people also have agency, and deserve the chance to fully exercise that agency independent of the value they can provide to capital? To acknowledge that other people have value in ways that can’t be extracted within the workplace and used to further enrich people who are already rich?

Our current mode of production creates a class of people who are treated as NPCs, mere bodies to be deployed in some warlords’ frenzied march to the top. But unlike the peasants in Dynasty Warriors, their behaviour is not preprogrammed, and they don’t have to put up with it forever.