February 20, 2019 (1394 words)

::

How can socialists claim they care about workers' rights but still use their iPhone? Easy: because socialism is a method of systemic critique, not a description of personal consumption habits.

Tags: the-left

This post is day 51 of a personal challenge to write every day in 2019. See the other fragments, or sign up for my weekly newsletter.

For some critics of the left, one compelling argument against socialism is the hypocrisy of its most visible supporters. Socialists claim to be against capitalism, and yet they partake in the products of the system they critique. They own iPhones or buy cheap clothes despite knowing the appalling working conditions behind their production. They eat McDonald’s, take Lyft or Uber, post on social media, or binge-watch Netflix despite being fully aware that they are contributing to the profits of a giant corporation. They criticise Western imperialism, yet they haven’t moved to Venezuela or North Korea.

Clearly their criticism is meaningless, so the reasoning goes, if even the self-proclaimed believers cannot follow their own professed tenets. They must be either deliberately lying, or simply misguided.

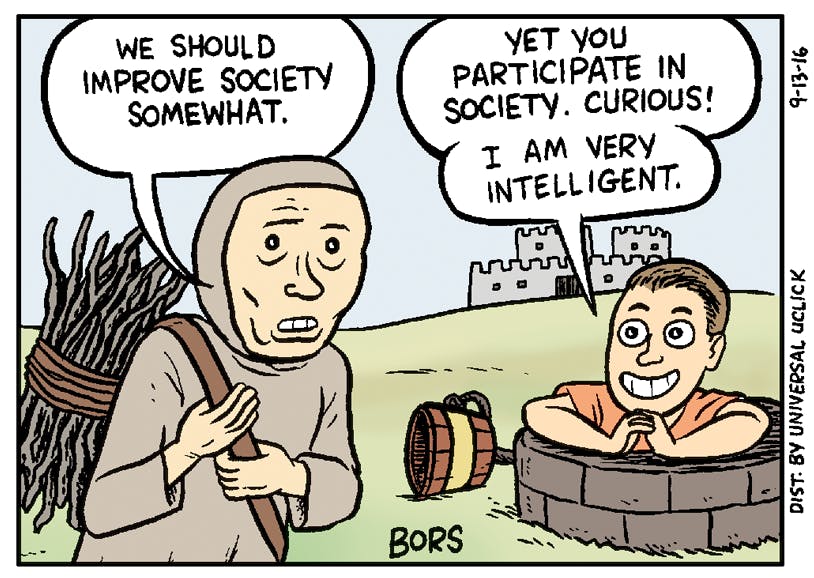

On the one hand, this is an obviously superficial argument, which could be easily dismissed right off the bat based on the comic below:

The iconic fourth panel of the “Mister Gotcha” comic, by Matt Bors for The Nib

The iconic fourth panel of the “Mister Gotcha” comic, by Matt Bors for The Nib

On the other hand, buried within this argument is a more subtle point that deserves to be drawn out. Why is it that people who criticise capitalism choose to partake in the system they detest so much? How do they resolve the contradiction between their beliefs and their choices?

(And maybe this line of reasoning is itself a reflection of capitalist realism, where the logic of the market is so fully absorbed that consumer choice is seen as the only valid source of change … as if a worldwide socioeconomic system were a commodity that could be opted out of on an individual basis, equivalent to buying Coke instead of Pepsi …)

The point is that the assumed “choice” here is not really a choice at all. It’s true that a lot of self-proclaimed socialists do participate in precisely the system they claim to want to abolish, as both consumers and workers. But why on earth would that invalidate their critique?

The totalising nature of capitalism is why it is so worthy of critique in the first place. If capitalism were somehow a niche phenomenon, confined to the margins of our socioeconomic system and accordingly easy to exit, then critique would hardly be necessary. This is clearly not the case; instead, what we have is a system so totalising that fully escaping it becomes effectively impossible for most of the world, at least without absconding from this mortal plane.

This is the point from which good critique departs. Any anti-capitalist critique worth its salt begins with a recognition of the difficulty of opting out of the system, and identifies this very difficulty as a crucial part of the problem. Anti-capitalism is a systemic critique, not a claim to the moral superiority of the individuals espousing it; the fact that it’s basically impossible to get a 100% ethically-sourced smartphone is an indictment of the system under which smartphones are produced, not a personal failing on behalf of those who own smartphones.

This is the essence of the oft-cited saying that there is no ethical consumption under capitalism. Of course, that’s not to say that all consumption is identically unethical. The point is that capitalism as a system precludes the possibility of ethical consumption.

It’s silly to accuse leftists of hypocrisy for consuming something that is produced unethically, when the crux of their critique is that capitalism provides the option for unethical consumption at all, through subjugating workers in the hidden abode of production. Pointing out instances of unethical consumption under capitalism doesn’t exactly discredit this critique.

Okay, so let’s say we accept that ethical consumption is impossible under capitalism. But why should that be an argument against capitalism? If ethical consumption is so hard to come by, why should we even care at all? Why even bother challenging a system that’s apparently so totalising and inescapable? Why not give up, and resign yourself to accepting that this is just how things are?

I guess that’s the part where morals come in. Anti-capitalism is a moral critique at heart - you can agree with its analyses of the mechanics of capitalism and still not give a shit if you don’t start from the same moral axioms. It’s a leap of faith, and it’s one that can only be taken in the dark, by yourself, alone with your own morality.

But then so once you’ve accepted the moral considerations, you’ll find yourself in a bit of a moral impasse. Because acknowledging the need to overthrow the system doesn’t immediately free you from that same system. Your ability to thrive as a human being is still mediated through this system, with all the attendant ethical horrors. We know the impossibility of ethical consumption in this system, but that doesn’t vanquish our desire to live as ethically as possible.

So what’s the solution? Should we all try to go off the grid, grow our own food, build our own houses? I don’t think so. As much as that can be a valid individual lifestyle choice, it’s not political activism. It’s an individualised form of escape that doesn’t do much to change the situation for those who don’t have the ability to escape. After all, part of the reason capitalism has been so durable is precisely its ability to generate, through various forms of dispossession, more subjects who have no choice but to participate.

If you actually want to change the system, you’re going to have to engage with the system. And that means participating in the system, sometimes begrudgingly, but sometimes willingly. Knowing that the system is dreadful doesn’t make you immune to its effects; we’re all still flawed neoliberal subjects of varying shades, susceptible to advertising and cultural expectations around consumption: buying a house, owning brand-name products, going on vacation. Existing under capitalism entails some degree of compromise with the tenets of the system, meaning that we are imbued - however unhappily - with the very consumer subjectivity we criticise.

Maybe that’s okay, in the end. Not in the sense that it means the system is good, but in the sense that we can still live with ourselves. What choice do we have? The system sucks, but if we’re to have any hope of changing it, we still have to live under it. And while I’m sympathetic to the view that we should try to consume as ethically as possible, I don’t think that it’s a precondition for activism, or that lapses in consumer judgment are a moral failing. I don’t think we need to be wracked with personal guilt every time we use Amazon. I don’t believe that guilt is an effective catalyst for political action, as guilt implies that blame is directed internally (within the consumer), whereas political mobilising requires directing anger outward, toward the actual source of the problem.

This post is going in all sorts of directions right now, and I’m not entirely sure where I’m trying to go anymore. I’ll end with the observation that we are all, inescapably, subjects of the system we are trying to critique. There is no higher vantage point to which we can decamp, where we will be free of the ideological fog of capitalist realism that blurs our vision even after we’ve named it for what it is. Recognising that the system depends on your continued consumption doesn’t automatically make it easy to stop buying dumb shit we don’t need that we know was produced under dubious circumstances.

This isn’t to say that all consumption is excusable, no matter how morally shaky. Nor am I suggesting that trying to consume ethically is pointless. It might make you feel better about yourself, which is not to be sneezed it, and it could even make things marginally better within the constraints of the system. I’m saying that it’s counterproductive to beat yourself any time you find yourself wanting to take an Uber or buy a pair of Nikes. It’s not really your fault, for one, when the whole system is set up to promote consumption despite the costs of that consumption on the environment, other people’s lives, etc.

Don’t be angry at yourself for wanting to consume. Be angry at the system that encourages this behaviour in the first place, and then locate the levers for systemic change.