GV4D4 - week 8

« Back to GV4D4These are my notes from November 14 for GV4D4 at the London School of Economics for the 2017-2018 school year. I took this module as part of the one-year Inequalities and Social Science MSc program.

The usual disclaimer: all notes are my personal impressions and do not necessarily reflect the view of the lecturer.

The Politics of Labour

Readings

Inequality by Anthony B. Atkinson (chapters 4-5)

Chapter 4: Technological Change and Countervailing Power

He’s basically saying that as more and more jobs get automated, the traditional way we conceive of labour & labour markets needs to change (as it’s drifting farther and farther away from its original purpose of producing/distributing scarce goods), but never actually reaches what I think should be the ultimate conclusion: that we need to socialise the means of automation.

He does have a good quote on the perils of being too reliant on technology:

Experience with robots leads us off on a path where they, increasingly, over time, replace humans, the trade-off becoming increasingly favourable. But we could have taken an alternative path where the human-service element was emphasised and the skills of people were increasingly developed. We have therefore to consider the implications of today’s production decisions for where we would like to end up in the future. Here, the motives of the firm, giving priority to the specific interests of its shareholders, may not be aligned with the wider interests of society, and we need to consider the role of countervailing power, taken up later in this chapter.

On the other hand, he thinks the state needs to intervene in innovation in order to assure continued human employment. This is decidedly not a post-work take. He also has a weird take on the Baumol effect—instead of seeing it as a totally normal and acceptable thing (an obvious side effect of increasing productivity in manufacturing etc) he sees it as something to be concerned about and thus ameliorated through increasing technological investment in service sectors? I agree with his conclusion but the logic is strange. Surely that conclusion can be reached without having to mention the Baumol effect at all. But maybe he’s just trying to convince fellow economists who can’t see the value in something unless there’s a price tag attached to it.

In the second part, he talks about the countervailing forces that prevent corporations from doing the right thing, and suggests that the state take into account distributional concerns when regulating market activity. He recognises that his proposals are “flying in the face […] of the economics literature” which, I have to say, is quite an astounding thing to fathom given just how (frankly) tame his proposals are. That says something pretty worrisome about the state of economics & the world today, I suppose.

Finally, he goes into the broader ideological shift that led to the decline of the influence of unions, mostly spurred by the passing of anti-union legislation between 1980-1993.

Chapter 5: Employment and Pay in the Future

- He advocates for a fuller employment market (in the sense of reducing involuntary employment) via state-guaranteed jobs as well as better pay

- Highlights the changing nature of work, mostly due to technology, but also due to changing views of work (more part-time, non-standard work)

- One problem in the UK re: unemployment is that no one has an unemployment “target” the way they have an inflation target

- Cites the WPA as a good example of guaranteed jobs

- Proposes various implementions of a jobs guarantee in the UK (where the govt acts as an employer of last resort)

- Recognises that giving everyone a job is not enough if pay isn’t fair

- The solution: giving labour more bargaining power

- Supports a (higher) minimum wage and maybe even a maximum wage (as a ratio)

- Wow, John Lewis top execs can only be paid 75x the average salary T_T the fact that this is considered “progressive” is depressing af

- Believes that statutory solutions to greater pay equity are neither sufficient nor necessary; instead, we should change public opinion & get firms to voluntarily adopt such policies

Comparative political economy and international migration (PDF) by Afonso Alexandre and Camilla Devitt

Published 2016. On the economic effects of immigration, distinguishing between LMEs and CMEs.

- last decade: 70% of workforce increase in Europe and 47% in US foreign-born

- immigration interacts with labour market institutions via:

- segmentation:

- migrants can be more willing slaves of capital (weaker eco/poli resources, thus accept worse terms)

- a way of reconciling society’s required protections (for natives) & capital’s need for flexible labour (it’s dumped onto outsiders)

- ex: 19th century, Irish migrants to England formed an “industrial reserve army” (Engels)

- ethnic, national divisions between migrants & native-born often exploited by capitalists to prevent united class consciousness

- complementarity

- the idea that certain policies/institutions are complementary

- ex: favouring of higher-skilled immigrants goes well with flexible labour market, lots of VC

- functional equivalence

- immigrants as a source of labour to “fill the gaps” (i.e., take the jobs natives don’t want or can’t do)

- lower end examples: child care, picking fruit

- higher end: doctors, academics, scientists, executives, engineers

- segmentation:

- LMEs have received more immigration than CMEs in general

- Streeck on post-Soviet migration to Germany: there was concern that trade unions wouldn’t be able to maintain their influence

- so immigration control was necessary for keeping the CME nature of the economy

- OTOH, the segmentation model suggests that migrants can help an economy absorb cost of recessions (by offloading to migrants…)

- Streeck on post-Soviet migration to Germany: there was concern that trade unions wouldn’t be able to maintain their influence

- Q: how does migration impact welfare state provision?

- migrants typically net contributors to pensions (since they’re younger)

- otoh, more likely to need social services (unemployment, housing, etc)

- Bismarckian systems more likely to exclude them, at least initially

- impact on training systems

- given that there are two ways for a nation to acquire skilled workers: training, or immigration

- exactly what Silicon Valley is doing right now with H1-Bs

- ofc this can have the effect of suppressing labour by making it harder to form unions

- ethnic/national divisions undermine solidarity

- plus those on visas with very limited rights (best example: H1-Bs) are in more precarious situations and can’t risk their job

- immigration is (obvs) not just a factor of econ growth—there’s a sectoral component too

- ex: Italy, Germany both had high unemployment & high (labour-based) migration in 90s

- large welfare states usually attract less low-skilled migrants (since less demand for them?) despite fears to contrary

- policy drift can result in more migrant labour, for ex in underfunded public services (care)

- LMEs seek migrants to enhance innovation, productivity, competitiveness; CMEs more conservative (protecting existing labour market)

- inverse relationship between openness to trade and immigration

- if you can’t import cheap goods, will try to import cheap labour instead (to make those goods)

- but if you CAN import cheap goods, domestic production of cheap goods declines -> need for cheap labour does as well

- relationship between trade union strength & immigration policy: stronger -> more restrictive

- in Nordic system, unions require full integration of migrants (in order to preserve their own strength) -> undermines employers’ attempts at segmentation

- in Bismarckian system, importing male migrant workers preferable to having more women in workforce (thus challenging traditional gender roles)

- otoh, the relationship isn’t clear; diff types of union movements react differently

- some unions support more immigration (perhaps as way to bolster declining memberships? or due to collaboration w/ employers)

- distinction between companies in tradeable and non-tradeable industries

- if more tradeable, more open to immigration (bring down prod costs)

- if less: fear of competition from foreign firms w/ foreign (cheaper) employees

- cultural aspects behind resistance to immigration

- Japan: desire for homogeneity even despite low birth rates & ageing pop

- conclusion: need more data to study “welfare magnet” hypothesis (authors seem to be skeptical of it)

A Common Neoliberal Trajectory by Lucio Baccaro, Chris Howell

Published 2011. Argues that neoliberalism has transformed industrial relations, even in CMEs that are typically thought to be more resilient. Following Streeck, wants to shift focus to understanding commonalities of capitalism rather than differences on a nation-state level. Features a bunch of case studies on industrial relations within certain European countries. Some notes:

- VoC approach not fully static—allows for convergence of CMEs into LMEs (opposite is much more unlikely)

- Streeck symbolises biggest break from standard comparative political economy

- rather than a focus on institutions, focus instead on the underlying logic of capitalism

- complex dialectic between stickiness of institutions & constant transformation (“permanent reinvention, change, and discontinuity”)

- neoliberalism has sent different nations on a common trajectory, even if their starting points & velocity are different

- the importance of institutional deregulation (liberalisation, individualisation) in order to (essentially) reduce power of labour & let the market take hold

- nonunion worker representation (bypassing traditional structures) is a way of weakening influence of unions & strengthening power of employers & employees should not fall for it

- in the UK, post-Thatcher:

- New Labour obviously didn’t really move away from Thatcher’s trajectory

- but still, some changes: statutory min wage; better family leave; more unfair dismissal protection; right to union recognition if ballotted support

- OTOH, this was mostly a focus on individual rights which did nothing to improve the state of collective bargaining

- the case of Germany is interesting

- did ok post-OPEC crisis, at least for a while

- problems started in the 90s, after reunification (partly due to high-skill, low-cost labour from the East)

- since then: overall weakening of labour (more bargaining at firm level, workers councils cooperate w employers)

Summary: no country is fully immune to the changes wrought by neoliberalism, and the state has played some role in all of them (it’s never just a natural outcome of the free market etc). The biggest change is for greater employer discretion (what David Harvey calls “flexible accumulation” in his Brief History of Neoliberalism).

Lecture

- in previous lectures, we focused on _re_distribution (mostly via the welfare state)

- now, we’ll focus on _pre_distribution—based on the market

- obviously the idea that there is a “natural” distribution of income, independent of the state or other factors, is extremely misguided

- market dynamics are affected by regulations (among other things) and in fact there is no Rawlsian equivalent of an original position for markets

- we’ll focus on wages, because they usually comprise the largest share of income (usually 60-70%)

- although welfare state institutions can also influence pre-tax inequality, we won’t focus on them as much

- rather than Gini, we’ll look at P90:10 ratios

- usually somewhat similar to Gini but different in a few cases, most notably South Korea (much higher P90:10 than you’d expect from the Gini)

- it has its flaws, ofc, since the statistic deliberately excludes those who aren’t making any income (thus unemployment levels are not taken in account)

- labour market factors that explain income inequality disparities

- the power of trade unions

- the existence of an employers’ organisation for unions to bargain with

- government regulation, especially employment protection legislation (EPL) which determines, among other things, how easy it is to hire/fire

- bargaining system differences between LMEs and CMEs

- in LMEs, it’s almost always decentralised and individual-level—no collective agreements, just one-on-one bargaining (with perhaps some flexible industry standards)

- whereas in CMEs, there are usually agreements between trade unions (or confederations of) and employers (or confederations of, called “social partnerships”)

- can be firm-level, industry-level or even national-level

- these can exist to some degree in LMEs as well, ofc

- example: academia, where lecturers are paid according to a city-wide scale (though LSE has its own scale as well, and individuals can negotiate higher pay)

- agreements might cover only members of the union, or everyone in the industry (by law)

- where there is more centralised bargaining, there is less wage inequality due to wage compression (following Meltzer-Richard logic)

- otoh, if higher-skilled workers leave (or potentially other workers, afflicted with Dunning-Kruger) then the coalition breaks down

- we can’t neglect how the setup of a welfare state might impact bargaining power

- if there’s a greater safety net, workers are in a stronger position

- thus we can’t simply take away the welfare state (the _re_distribution aspect) & expect inequality levels to stay the same

- union density has lately been declining in both Germany and the UK (though the UK is farther ahead along the trajectory)

- in a liberal labour market, people are treated more like commodities

- inequality is accepted as a natural fact of life

- only those at the very bottom are protected via means-tested welfare benefits (and very reluctantly)

- wages more elastic, following laws of supply and demand (think Uber drivers)

- more freedom of hiring/firing

- good for high-skilled workers in less saturated fields, who can easily switch jobs to pursue higher wages

- you can see the vertiginous salaries in Silicon Valley as the result of California being an at-will employment state (and ofc buoyed by massive amounts of venture capital)

- bad for low-skilled workers in saturated fields

- benefits:

- theoretically, efficiency gains means that the market is more likely to clear

- i.e., no long-term involuntary employment (assuming no minimum wage, which ofc is a silly assumption because this means that the cost of reproduction of labour is abstracted away …)

- otoh, if we look at labour force participation of prime-age male citizens across OECD countries, this number has fallen a lot lately

- the US, in particular, has one of the highest unemployment (or rather: not employed) rates

- reasons for inequality in an LME:

- Sherwin Rosen’s superstar effect (articulated in this 1981 paper for highly visible professions)

- academics, sports, music, etc

- the top performer in this field gets all the fame and attention so there is a huge (and not necessarily “merited”) gap between the top and the second

- you end up with a winner-takes-all market in which distribution is totally out of proportion to relative differences in standing

- results in an inefficient allocation of resources (due to competition for access to the top performer), where the social gains are not in line with the private gains (accrued by the top performer)

- Sherwin Rosen’s superstar effect (articulated in this 1981 paper for highly visible professions)

- in CMEs, there is less competition among firms when it comes to labour—standardised wages are more accepted

- can come in the form of a general union-employee agreement, or implicit collective bargaining by “wage leaders” who set the wages for the rest of the industry

- incidentally, some unions (esp in Germany) have been keeping wages down, partly in order to prevent capital flight (so they can play a conservative role as well)

- when this bargaining is on a large-scale, it has to take inflation and unemployment concerns into account as well

- theoretical negatives (all of which I kind of disagree with)

- efficiency disadvantage as markets are suppressed

- if labour is too empowered, they can command ever-higher wages which can essentially become rents paid to workers

- can disincentivise individuals from investing in training/education in order to acquire higher skills (if they’re not going to get paid that much more)

- otoh: wage rises are dampened; inflation is contained; less inter-firm poaching

- ofc the CME model has been under strain ever since the 80s (though with different outcomes in different countries)

- even the Scandinavian countries are affected, though they’re weathering the storm better than some others obviously

- centralised bargaining has been slowly moving down the hierarchy and becoming more decentralised

- pressures due to

- globalisation (esp China and Eastern Europe—low-wage competition)

- tertiarisation (rise of service industry compared to, say, manufacturing)

- feminisation of the workforce (women entering workforce + changing composition of trade unions which were traditionally male)

- political/economic landscape changes as neoliberal ideas have become hegemonic (commodification of everything)

- result: rising inequality due to lowered wages at the bottom and rising wages at the top due to (globalised) superstar effect

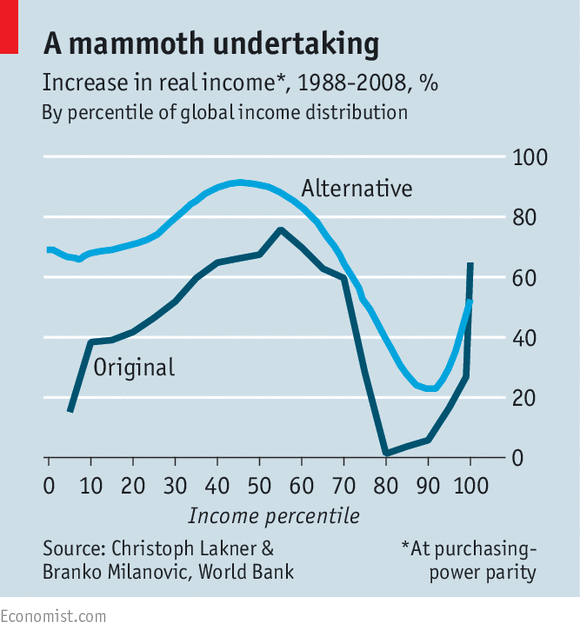

- Milanovic’s elephant curve:

- the standard interpretation of this is that the very rich have done quite well from 1988-2008

- and a lot of previously poor people have been lifted out of poverty (most notably in China)

- but the middle classes of the Western nations (bottom of trunk) have suffered

- though this interpretation has some criticism, e.g., this one from PIIE which shows something very different if you take out Japan/China/the ex-Soviet countries

- reasons behind recent changes in inequality

- labour market changes partly due to technology (automation)

- also immigration, which can affect labour markets in different ways

- can make markets more efficient (“matching” or “complementarity” like when migrants take jobs natives wouldn’t take)

- demographic pressures: ethnic/gender-based fractionalisation of the labour force can foster divisions

- plus anti-immigrant sentiment can lead to the rise of right-wing parties who oppose both immigration and redistribution

- this can also impact the Meltzer-Richard model since migrants (typically lower paid) don’t have voting rights

Seminar

- I brought up Kalecki’s whole thing on the problems with full employment & how you can never have that because it empowers labour too much

- otoh, different nations have different equilibrium points in the capital/labour struggle so we should consider why that is

- on EPL: hasn’t changed much 1985-2008 for permanent workers, but loosened for temp work esp in scandi countries

- union density rate fallen almost everywhere except spain (historical outlier, due to political history, from 10% to 15%)

- biggest fall: New Zealand, 70 to 20

- note this is MEMBERS not necessarily coverage (tho if there’s a strike called, everyone goes on strike)

- otoh, chart of coverage rate: france is near the top, has increased; some at the top have increased coverage; LMEs fallen

- why do corps agree to deal with union? saves admin overhead/risk of industrial action etc

- also germany case: in employers’ interest, keeping wages down

- plus reduces chance of poaching

- so why do LMEs not allow union rep??? cus historically, less centralised, not high enough level for positive externalities

- cus market can discipline workers more than agreements can

- does the chart of coverage rate (increasing in some, decreasing in others) contradict the last reading?

- not necessarily: misses the level of these agreements (decentralised) + character of them (pro-worker or not)